The amazing story of Marko Feingold

When I asked Marko ‘Max-Mordechai’ Feingold, the President of the Jewish Community in Salzburg, about his feelings after lying a “Stolperstein” carrying the name of another Nazi-victim, the old man just put his hands on the left chest, as saying: “my heart stops beating for a moment”. This was the 150th time his heart lacked this very heartbeat since he initiated the project in his hometown in 2005. Not the healthiest thing to do when you are a Holocaust survivor and you approach the age of 99. But Feingold does not care.

For the Hebrew version of the article – Click Here

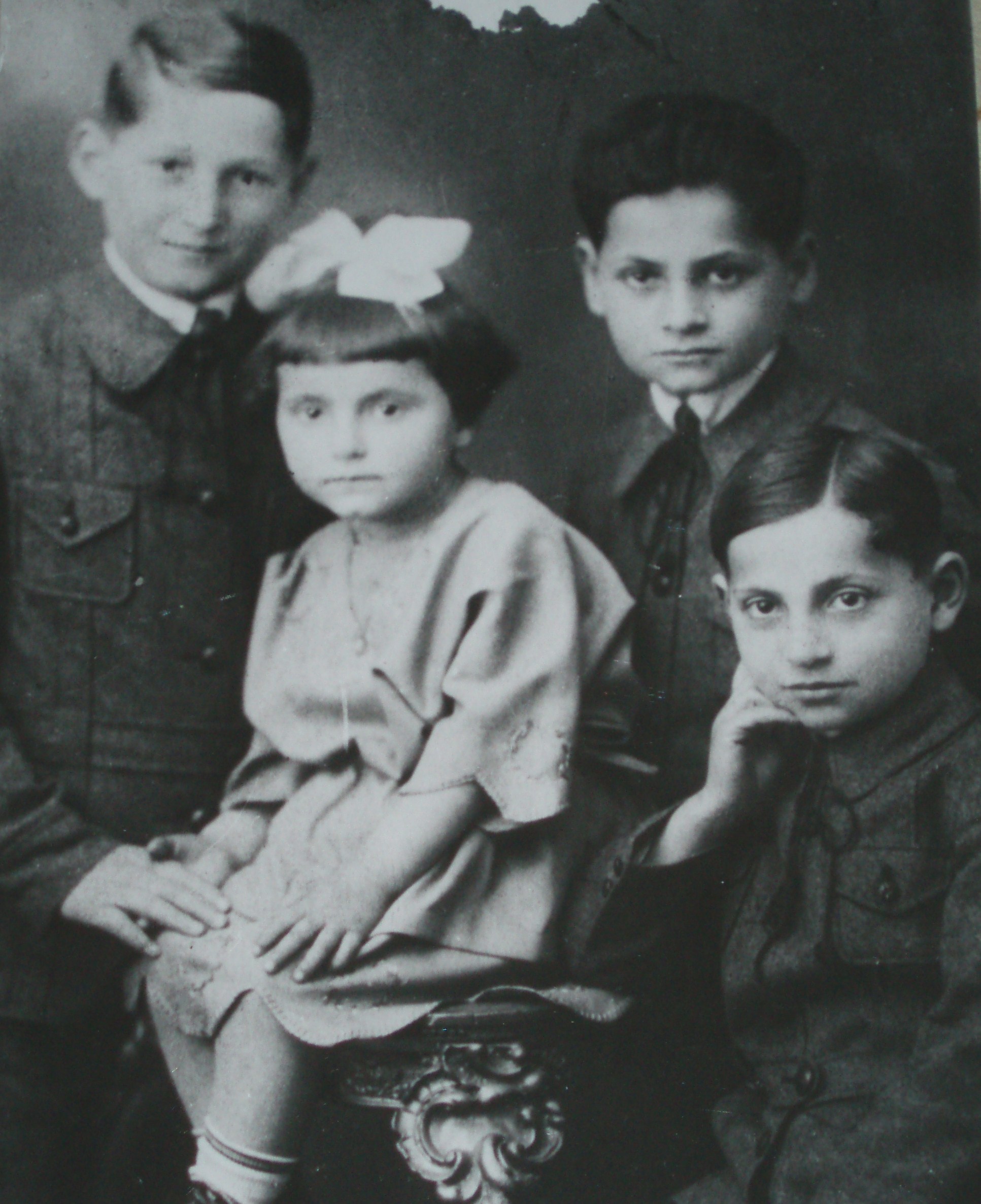

He was born in 1913, as a citizen of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, to Heinrich, a railway worker, and Zilli, a housewife who passed away in 1936. Marko was the third boy after Fritz and Ernst, and the big brother for Rosa. Growing up in Vienna, he concluded a traineeship in commerce and sales. The economic downturn in Austria in 1932 forced Marko and his brother Ernst to leave to Italy to make a living. A terrible coincidence led to his arrest by the Germans who invaded Austria in the beginning of 1938, just when the two brothers came back to prolong their Italian visa. The family was forced to leave Austria for Prague, and then on to Poland. A failed attempt to escape, led Marko and his brother Ernst to a polish prison – and eventually to the labor camp in Auschwitz. Only after the war, Feingold found out that his father was killed in 1939, during the German bombing on Warsaw. The fate of Rosa and Fritz is still unknown.

Q: Did you know what awaits you in Auschwitz?

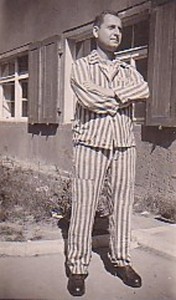

A: “I was the first Austrian prisoner ever to step foot in Auschwitz. I had the feeling that my end is near, since the rumor was that Jewish prisoners do not survive more than 3 months in this place. I remember when I got there; they beat me and burned my hair with a candle. Auschwitz was back then only under construction. Due to the work and the hard physical conditions, I lost my weight and went down to 30 Kg. After two months I was unsuitable for work, but I was still sent together with Ernst to the labor camp Neuengamme, in northern Germany. We got there during the winter, which was very cold and humid. We were forced to dig with our bare hands a channel between the bricks factory nearby and the city of Hamburg. At this stage, I was so called “gas-able” and was about to be sent to the gas chambers. But the crematorium in the camp wasn’t ready yet. So I was sent with 250 other prisoners on the train to Dachau in the south. Only 75 of us survived the trip that lasted 2 days. This was the last time I saw Ernst. Only in 1950, while I was testifying about Neuengamme, I was asked to pick-up his death certificate. Apparently he died there in 1942, by the time I’ve been already in Buchenwald.”

Q: How did you escape the execution in Dachau?

A: “During the journey to the camp I managed to recover somewhat, and got on my feet again. I was positioned there as a translator in a selection hut. Not because I spoke many languages – if somebody asked you something there, you knew automatically that he wanted more food. One day, a Kapo I ran into told me that Jews were not allowed to hold any positions in Dachau. So he sent to me to work in the garden. There, my condition deteriorated further due to the hard work and the clogs we had on. Soon enough my feet got infected and I was housed among the walk-incapable prisoners. Back then, the Nazis had a system to transfer prisoners from camp to camp. Those who collapsed on the way were shot. This way I was transferred to Buchenwald.”

Q: This is the camp where you actually spent the longest time in.

A: “Yes.

I got there in September 1941. We arrived at the train station of Weimar in the evening. From there, we were force

d to march 8 km up the mountain into Buchenwald. Once we reached the camp, we had to walk another 2 km inside. In the beginning I was put to work in the quarry. The Germans needed flat rocks for their roads, so we used to fight among us over ‘the good stones’. Besides that, every little mistake was punished there with death. Afterwards, I joined the ‘Singing Horses of Buchenwald’, a group of prisoners whose job was to sing while they push heavy wagons up the mountain. In August 1942, I started to work as a bricklayer and became pretty good at that. At a certain point I could even leave my post and exchange cigarettes for bread. This gained me a bad reputation among the communists in the camp, although I did it because I was hungry. And when you are hungry, you will do anything. This way, I gained additional 10 kg.”

Q: How did you learn to get along in these difficult situations?

A: “Between the ages 12 and 14, I used to hang around the circus next to my house. There, I got to meet all the workers who many of them were considered to be very dubious. So I learned from them how to become the biggest gangster among all other gangsters.”

Q: What do you remember from the camp’s liberation?

A: “During the American siege on Weimar in April 1945, we slowly noticed that there were less and less S.S soldiers in the camp. In the afternoon of April 11th, we realized that all the guards have escaped. Suddenly a friend of mine called me out ‘because the Americans give out food’. The weird thing was: I was not even hungry.”

Assisting the ‘Bricha’

Just like in every coincidence that has shaped his life, it was again the fate that brought Marko Feingold to Salzburg. He initially intended to return to Vienna, his hometown. But a blockade of the Red Army made him get off the bus in the scenic city. In the years to come, he committed himself to the “Bricha” (in Heb. “Escape”) movement that acted for smuggling Displaced Persons (DP), i.e 250,000 Jewish camp refugees, from the DP-Camps in central Europe, through Italy and then to the Land of Israel.

“I was working in a kitchen that cooked for non-Jewish refugees, receiving 2,000 Schillings per month”, he explains, and adds with a smile: “back then, there were more Jews in Salzburg than inhabitants”. One day, American officials came to him, claiming that the Jews are refusing to eat their meat and demanded vegetables instead. And what firstly started as a simple food exchange, led Feingold to meet Asher ‘Arthur’ Ben Natan, who later became the first Israeli ambassador to Germany, and Dr. Abba Geffen, later to become a prominent Foreign Ministry deputy. The two were in charge on the ‘Bricha’ from Austria and Salzburg. Feingold has turned out to be especially suitable to the mission since he spoke Italian and knew well how to get things. For instance, thanks to a few German army vehicles, which Feingold managed to attain from the Austrian authorities, the ‘Bricha’ succeeded to smuggle 5,000 Jews over the Italian border, in a period of three months.

Q: Weren’t the Allies suspicious of what you were doing?

A: “The eastern part of the border was under British control. They had an obvious interest to prevent us from doing our job. The French, on the other hand, closed their eyes. Once, I found a rocky passage through the mountains in an area which the Americans controlled. There, we could already move freely. Many times we had to lead the refugees by foot through the Alps, in terrible cold without any equipment. We used to do it at night, because they were afraid of the heights.”

Q: How many Jews did you help?

A: “Around 100,000 people managed to go to Israel with my help. Most of them don’t even know that it was me.”

Q: Didn’t you want to join them?

A: “My roots here are too deep. I am proud to be a ‘Salzburger’ and I also received many honorary titles. Besides, I don’t think I could have reached the age of 99 anywhere else. Although the thought about it is always here.”

The battle over the memory

The ‘Bricha’ activities ended by 1948, and Marko Feingold had to face, once again, a difficult economic reality. So he opened in Salzburg a fashion shop, and began to tell his story at every opportunity he got. In these years, he was in a big fight with the local Jewish community and the sides barely kept in touch. According to Feingold, the presidium of the community was jealous of him, because he was the most famous Jew in the city. “Only in 1977, when I retired, they realized their mistake and made me to vice president. 2 years later I became the president”, he says.

Ever since, he is (together with his wife Hanna) on a constant mission to commemorate the victims of the Holocaust, and to fight against those who try to deny it.

Q: How did you cope with extreme right winged politicians that became in Austria pretty powerful over the years?

A: “Look, in Germany for instance, a man like Haider could never become as big as he was in Austria. Why? Because the most of the population still thinks the way he did. Salzburg is a good example for that. There were always politicians that took advantage of people’s ignorance. It became already a tradition in this country. We could have gone on with our lives a long time ago if the Austrians have said that they knew about the Holocaust, but couldn’t do anything. Instead they say they didn’t know about anything – that’s nonsense! The big problem is that they never really dealt with their past. The first generation didn’t pass-on anything. So the generations after remain ignorant. Sometime I lecture in front of children and it’s like they never heard of WW2.”

Q: Do you have any plans for your 100th year?

A: “I will continue to work with the children about the past, the way I did it in the last 67 years. People here see me as a phenomenon: ‘how can one survive so many camps, and still have the energy to go on?’ I live to tell my stories, and believe me – there are stories which you wouldn’t believe. But there is no one left to tell them, only Feingold!”

I¡¯m still learning from you, while I¡¯m trying to reach my goals. I absolutely liked reading all that is written on your blog.Keep the stories coming. I liked it!

Just wanna tell that this is extremely helpful, Thanks for taking your time to write this.

Do you have a spam problem on this website; I also am a blogger, and I was curious about your situation; we have developed some nice methods and we are looking to exchange methods with others, please shoot me an email if interested.

By far the most concise and up to date information I have found on this topic. I am glad that I navigated to your page. I have to say. Actually not often do I encounter a blog that¡¯s each educative and entertaining.

I wanted to post you a bit of remark to finally thank you very much once again for all the fantastic opinions you have provided on this website. It¡¯s simply incredibly generous of people like you to supply without restraint exactly what a number of us could have supplied for an ebook to make some dough on their own, most importantly given that you could have done it if you ever desired. Those smart ideas also worked to become a great way to recognize that the rest have the same interest really like mine to find out a whole lot more with respect to this condition. Certainly there are millions of more pleasant times in the future for individuals that view your blog post.

This is really a tremendous web site. Very nice post. I just stumbled upon your weblog and wished to say that I¡¯ve truly enjoyed surfing around your blog posts. In any case I will be subscribing to your feed and I hope you write again very soon! mashpeeopenmarket” iphone 4s tethered jailbreak.